How Indigenous fashion designers are taking control and challenging the notion of the heroic, lone genius

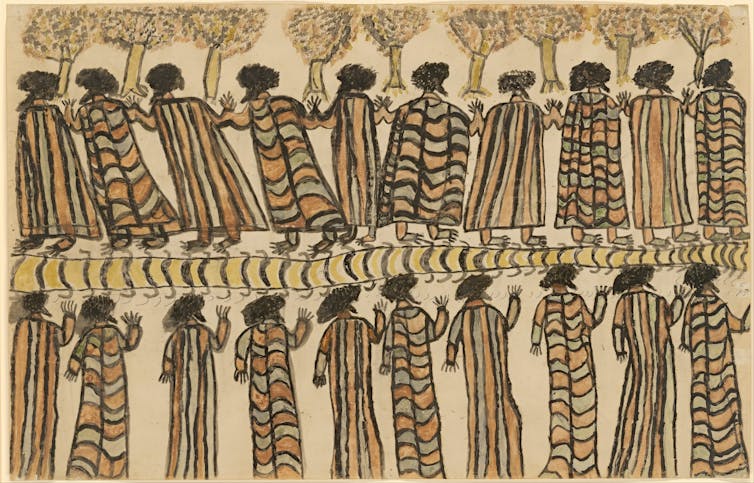

Indigenous Australians have influenced modern Australian dress since first contact. From possum skin cloaks and booka kangaroo capes to shell necklaces in Tasmania, Europeans have been fascinated with Indigenous materials, skills and aesthetics.

They have stolen, purchased, borrowed and worn them for more than 200 years.

In turn, Indigenous Australians have at times enjoyed wearing soldiers’ red jackets as battle spoils and possibly mocked the Europeans by wearing their top hats cockily in the early streets of Sydney.

Wikimedia Commons

Later, as First Australians were dispossessed from their lands and herded into reserves and missions, clothing was imposed on them, ranging from shapeless “mother hubbard” dresses for women to shabby but respectable woollen two-piece suits for men.

Traditional dress practices, along with ceremony, language and music-making, were often banned by the colonisers. Missionaries often taught western-style leatherwork to men and needlecraft to women – yet powerful hybrids of self-determined dress also emerged, expressing subversive gestures and quiet resistance.

In the mid 20th century, missionary nuns in Far North Australia began to allow Indigenous women to craft their own textiles. Brightly coloured fabrics were the result, with unusual combinations of motifs. As Indigenous Art Centres were developed across Australia from the 1970s, mostly in remote communities, the fertile hybrid of painting and textile design generated wholly new looks – leading to the Indigenous textile revolution.

For some time, Indigenous Australian art was often seen as the future of a distinctively Australian design, as evident in the 1970s energy of Jenny Kee and Linda Jackson, but on the whole, Indigenous design was not recognised in its own right. This is now changing – Indigenous fashion design today is being shaped by First Nations people at every level.

Dylan Buckee

Last weekend, the Darwin Aboriginal Art Fair was held on Larrakia Country. For the second year in a row, a major fashion parade more akin to a performance filled Darwin’s large Convention Centre. The fashion event From Country to Couture, held on 7 August, showcased fashion and textile design. But there was a very big difference from the way such a parade would have appeared in the 1980s or even the 1990s.

Indigenous Fashion is about a new framing of self-determination. From Country to Couture was designed, coordinated, produced, curated and mobilised from wholly Indigenous standpoints. This was apparent in many striking ways – from the inclusion of Indigenous models, to the deep strains of a “black power” music track.

Dylan Buckee

This year’s creative director of the event was Grace Lillian Lee, whose own designs are in major collections including the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences (Sydney). Grace also leads a project called First Nation Fashion + Design which nurtures relationships between Indigenous artists and the fashion industry. Lee notes that she is “empowering black women and men to have their voices in the fashion space, which doesn’t always have to be overtly political, and can just be beautiful, and a lot of fun”.

Lee worked with dozens of artists, mainly from remote Indigenous Art Centres. Textile approaches ranged from silkscreen, batik, weaving, natural dying, digital printing, and embroidery. Some of these collaborations had the energy of new experiments, and others are ongoing.

The anniversary collection of Tiwi clothing label Bima Wear, in collaboration with Clair Helen celebrated 50 years of the women’s creative enterprise. The designs worked with the quintessential geometric patterns of Bima in bold combinations. The message was as much about ethical, community-led industry as it was about beautiful textiles and clothes.

James Taylor

Fashion has always been collaborative. It relies on the varied skills of textile designers, manufacturers, hidden hands or makers (petits mains in French), stylists, marketers, photographers, distributors, as well as designers. Yet since the late 18th century, the idea of fashion has been generated around one powerful individual – the high fashion designer.

Indigenous fashion challenges this focus on hero designers – many of whom are men in western society. Based on deep community engagement, it challenges the conventional understanding of the fashion designer as sole, individual author and draws on the talents of large numbers of women.

As much a cultural performance as a fashion parade, Lee’s Darwin event featured a set and a narrative of smoking, burning, and regeneration to thread the six collections together, interspersed with dance performances by Luke Currie-Richardson and Yolanda Lowatta.

From Country to Couture highlighted how the success of the textile design movement in remote Indigenous communities has shaped high-end fashion in Australia. But it also signalled a new way forward, grounded in community relationships, for Indigenous fashion design.