Indigenous Fashion Week Toronto is healing and resurgence in action

Indigenous people from across Turtle Island and beyond recently gathered on the traditional territory of the Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee in Tkaronto for the inaugural Indigenous Fashion Week Toronto (IFWTO).

After decades of smaller endeavours (Chi-Miigwetch to the Elders, forerunners and friends who laid the groundwork), a fully realized IFWTO has come to fruition. Founder and artistic director Sage Paul, along with developmental director Kerry Swanson and producer Heather Haynes, launched a beautiful new festival that centres on community and land.

It was not your typical fashion week.

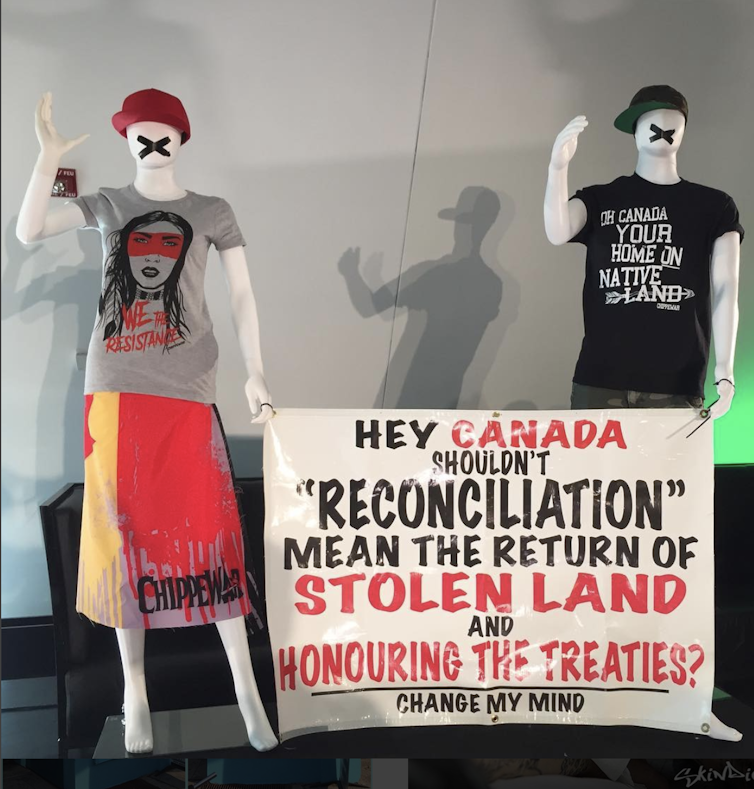

Signs that Indigenous people do fashion differently appeared early at a preview hosted by the Royal Ontario Museum. Fresh off its installation at a nearby Toronto intersection, Jay Soule (aka Chippewar) hung a sign between two silenced mannequins that asked, “Hey Canada shouldn’t ‘reconciliation’ mean the return of stolen land and honouring the treaties?”

Chippewar/Instagram

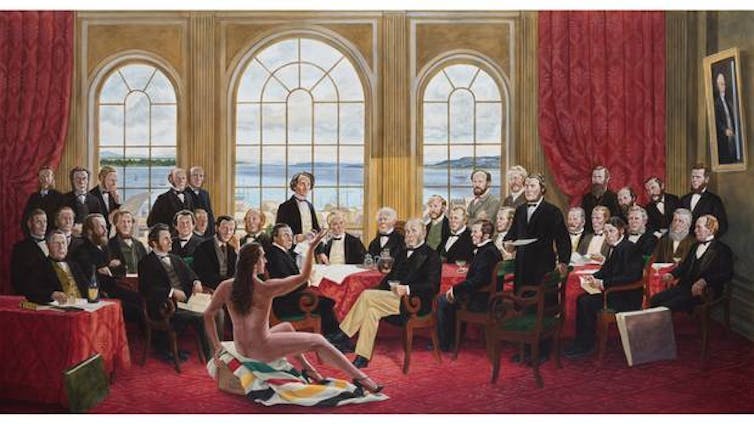

A few days later at a reception hosted by the Lieutenant Governor of Ontario, the thunderous songs and spoken words of Rosary Spence and Tantoo Cardinal reverberated through the halls of Queen’s Park. The scene recalled the disruptive power of a painting by Kent Monkman, who came to talk about his recent collaboration with Jean-Paul Gaultier, a noted cultural appropriator.

(Kent Monkman)

Four days of runways

Four days of runway shows were organized around moon phases — New Moon, Berry Moon, Harvest Moon and Frost Moon — which honoured emerging talent, regalia makers, matriarchs and northern designers respectively.

As an Ojibway PhD student studying the role of clothing in colonization, and Indigenous fashion as a mobilizer of cultural and economic resurgence, I was honoured to moderate IWFTO panels and to witness the workshops and runway shows.

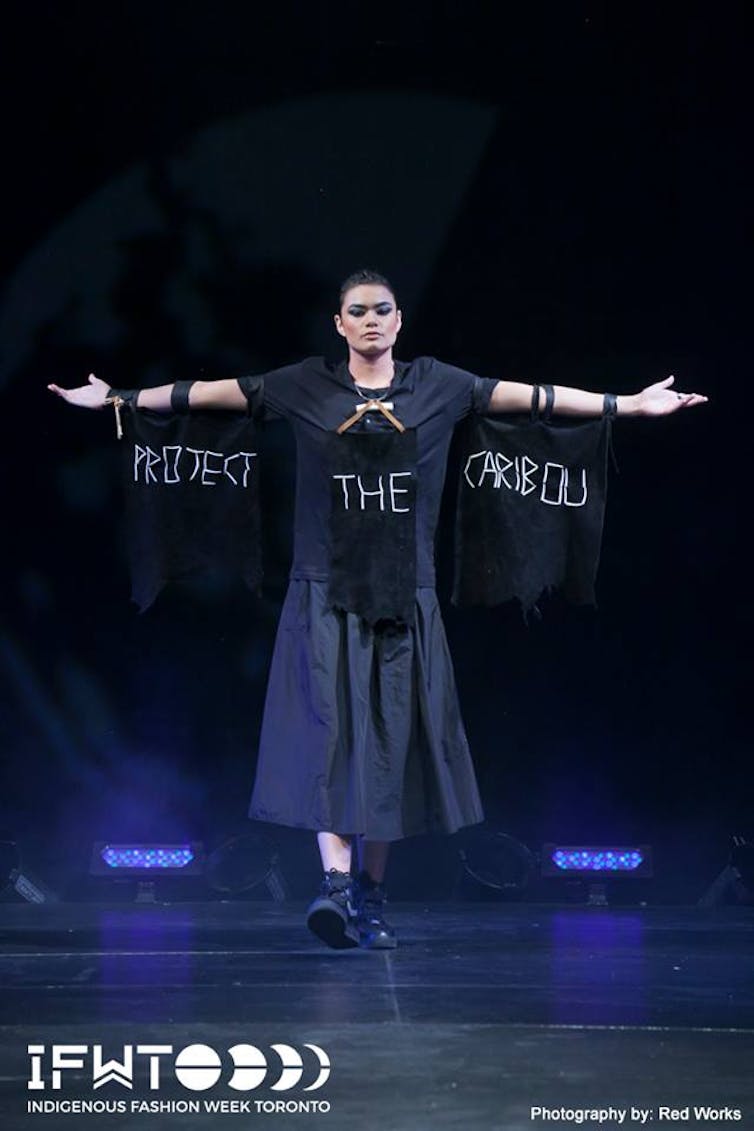

(Red Works Photography)

All designers put their heart and spirit into their clothing and honoured the past while looking to the future. My personal favourites included: Warren Steven Scott (Nlaka’pamux, Toronto) of Comrags, whose collection is deeply rooted in family and community and pays homage to the clothing of his aunties (who helped with the crochet); and Tania Larsson (Gwich’in/Swedish, Northwest Territories) a founding member of Dene Nahjo, a non-profit organization that focuses on cultural revitalization projects in the North, like urban hide tanning workshops in Yellowknife.

Larsson’s “Protect the Caribou” piece spoke to the interconnectedness of our relations: Without caribou, there is no Indigenous fashion, or food sovereignty or existence itself.

(Red Works Photography)

Interconnectedness was also a lesson shared in workshops on black walnut dyeing with Carola Jones, and ravenstail weaving from the east led by Meghann O’Brien and Navajo rug weaving from the west led by Barbara Teller Ornelas and her sister Lynda Teller Pete.

Holistic connections

In a panel, Jones and Ornelas discussed the significance of culture, story and process in their practice. We found that common among our Nations is an innovate frugality that comes from a deep respect towards land. Knowledge about plants, growing seasons and sustainable agriculture is at the heart of what makes Indigenous clothing so healing.

(Red Works Photography)

This is the brilliance of Indigenous design: It is inherently and holistically sustainable, and intimately connected to a web of human and non-human relations. It is also the significant depth lost when cultural (in)appropriation occurs, the topic of a fiery panel with Jesse Wente, Ariel Smith (Native Women in the Arts) and fashion lawyer Anjli Patel.

Teachings about ethics, roles, responsibilities and values are embedded in Indigenous design processes and lost when appropriated. And unless we fix the radically inequitable power imbalance this will not change.

This panel touched on issues such as institutionalized and normalized cultural theft, the lack of legal protection for Indigenous cultural knowledge, and the role of online social media activism in challenging the fashion industry.

Cultural appropriation is not an issue of intellectual freedom or free speech but of colonization itself, the panel concluded. They then discussed Indigenous sovereignty, solidarity with Black Canadians and revolution.

Indigenous futurisms

Indigenous futurisms and the imaginative power of science fiction was the topic of the last panel with Elwood Jimmy, Jeneen Frei Njootli and Skawennati.

We mused on questions posed by Jarrett Martineau on the electronic episode of CBC’s Reclaimed: “How do you imagine the future? What do you want it to look like? And how do you get there?”

(Red Works Photography)

We discussed what Indigenous design can contribute to a sustainable future that seems increasingly unlikely, what our clothing might look like in the future and how technologies of communication, extraction and manufacture might be harnessed by Indigenous peoples.

A chance to move forward

As our gathering concluded, the resounding sentiment was that IFWTO felt like imagineNATIVE in its early years. The film and media arts festival, now in its 19th year, is nationally and internationally recognized. This provides much hope for the future of Indigenous fashion in Tkaronto, Turtle Island and beyond.

That the team pulled off such a comprehensive event in a short amount of time is impressive. Even more incredible is that they carved out space for gathering and celebrating our culture, which, as Jesse Wente pointed out, was illegal for nearly 75 years under the Indian Act.

It is so rare that we gather like this. Early settler-Canadian colonizers saw the power in our numbers. When we gather we strategize, mobilize and revolutionize — not to mention socialize! We need to do it more often.

The four days of IFWTO left me exhausted but spiritually nourished. It is a shining star in a beautiful constellation that guides us forward.