Why women with HIV are persistently invisible – and how we can challenge it

The night before International Women’s Day, I volunteered behind the bar at “A Catwalk for Power, Resistance and Hope”, a fabulous fashion show for women with HIV organised by ACT UP London Women (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), and Positively UK, an organisation that runs peer-led support groups for people with HIV.

After a poetry reading by the incredibly talented writer and motivational speaker Bakita, these women led the call and response chants, derived from the anti-apartheid movement, of “THE POWER! – IS OURS!” and “AMANDLA! – NGAWETHU!” in front of a packed-out house at London’s Brixton East. Then the main show began: 25 women with HIV strutted their stuff on the runway with confidence, humour and pride.

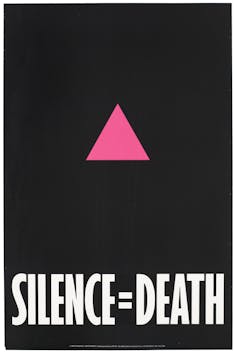

In her introduction, Silvia Petretti, an AIDS activist and deputy CEO of Positively UK, described how this fashion show was a huge step for women with HIV. “Openness about HIV can lead to being harshly rejected, and even being at the receiving end of violence,” she said. Positively UK was founded in 1987 (then called “Positively Women”) by two women with AIDS who had noticed the paucity of services for women with HIV, most of which were responding to the devastating impacts of AIDS on the gay community.

ACT UP London Archive, 2018

Petretti continued with some illuminating facts on women with HIV. 18m women across the world have HIV, making them the largest global demographic. In the UK, women with HIV make up 31% of all cases, the second largest group, “although you rarely hear about us”, and 80% of those women are black or from other ethnic minorities.

She also spoke about how women with HIV are disproportionately burdened by poverty, the impact of austerity and welfare cuts, racism and migrant hostility; and highlighted the links between HIV and violence against women. One study conducted by Homerton Hospital, Hackney, found a 52% prevalence of intimate partner violence among women with HIV. This, Petretti stressed, is “more than double that of the general population”.

In defiance of these devastating statistics, the event contested any status of “victimhood” for women with HIV, showing instead their incredible power and presence as they walked the catwalk. One wore a red shawl with “I AM HERE” inscribed on the back. Another shimmied and goose-stepped her way down the runway with a cheeky smile on her face, the whole room laughing with her. They were all totally in control, the audience whooping and cheering as the show continued. It was an absolute privilege to be there, to witness such a beautiful celebration of empowerment and the joy of living.

ACT UP London Archive, 2018

Unrecognised, unheard, unseen

Especially so because I have spent the last four years researching the invisibility of women with HIV/AIDS as part of my PhD, in which I examine the art of the American AIDS crisis. In particular, I looked at two exhibitions on women with AIDS, Until That Last Breath: Women With AIDS, a selection of photographs by the photographer Ann P Meredith, and Overlooked/Underplayed: Videos on Women and AIDS by various artists. Both exhibitions were held at New York’s New Museum of Contemporary Art in spring 1989, and both are missing from many accounts of the history of art responding to HIV/AIDS.

This artistic invisibility parallels a medical invisibility. AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome), is diagnosed by the presence of HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) in the blood, a T-cell count of less than 200, and the presence of two opportunistic infections.

But it was not until 1993 that AIDS, as defined by the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC), included opportunistic infections specific to womens’ bodies. This meant that prior to the change, some women with AIDS could not be diagnosed as such, rendering them medically and socially invisible. As described in Jim Hubbard and Sarah Schulman’s film United in Anger: A History of ACT UP, this change in 1993 came after four years of activist campaigning by ACT UP and other community groups, which eventually forced the CDC’s hand. Women with HIV and their queer allies alike fought hard for these basic rights.

In Sue O’Sullivan and Kate Thomson’s book recounting the founding of Positively UK, researcher Emily Scharf writes:

Why are women invisible? When we begin to ask this question, we see through the ‘spotlight’ of HIV all the problems that exist in our societies worldwide, including the familiar ones for women. HIV highlights all the issues around womens’ positions in society: often poorer; less access to health care for themselves; little support in their roles as carers for others; and in less powerful positions to negotiate relationships, including the sexual aspects of relationships, most specifically safer sex.

Wellcome Collection

The invisibility of women with HIV is the result of a complex interplay of violence and discrimination.

At the catwalk event, there were polite requests stuck around the walls asking that the audience not take any photographs to protect the privacy of the women, many of whom had not disclosed their status to anyone outside their support group. The history of HIV/AIDS is a history of violence, and in today’s world, violence against women is persistent and widespread, perpetuating stigma which silences and disempowers women with HIV.

Speaking up

Catwalk for Power was all about empowerment and pride. It was the product of months of workshops at Positively UK with ACT UP Women, where women with HIV talked about their experiences, wrote poetry, learned about the history of HIV/AIDS activism, “stitched and bitched” as they made their costumes all the while discussing, arguing, laughing together.

The anti-apartheid activist Steven Beko once said: “The most powerful tool in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.” Petretti told me how in her view, this sums up what events like the catwalk show can achieve for women with HIV:

It has enabled us to shift our awareness and embody the fact that we are agents of change, we can overcome stigma, and create a world that treats us with justice and respect, and it starts with us feeling confident and demanding it.

Prior to the event, which was choreographed with the help of the incredible runway coach Madam Storm, the group had made a set of masks that they were planning to wear on the runway, to cover their faces at the moment when they would be openly seen as women with HIV.

At the end of the show, the pile of masks was still there on a table backstage, untouched. They had all walked out without them.