Friday essay: Chanel’s complex legacy

Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel, friend of artist Jean Cocteau and lover of musician Igor Stravinsky, transformed women’s fashion across the world. Pablo Picasso said of her: “Chanel is the woman with the most sense in Europe”. Chanel’s fashion vision transformed both women’s appearances and definitions of luxury for the 20th century.

How did she pull this off, what is the continuing attraction, and how do we recognise her complex background, difficult choices and ongoing legacy?

With the opening of a new show, Gabrielle Chanel: Fashion Manifesto, at the National Gallery of Victoria, curated by Paris fashion museum the Galliera (supplemented with works drawn from the NGV’s collection), Chanel’s life and work are in the spotlight once more.

Who was Coco Chanel?

Coco Chanel was born in 1883 in Saumur, France, the illegitimate daughter of a street vendor, who struggled to raise her. She lived for a time with nuns, whose white linen and fine sewing influenced her later approach to good dressing.

Chanel began her life as a singer in cabarets, where she sang a tune that gave her the nickname “Coco”. She took up a series of lovers, not unusual for struggling women in that time, which gave her the capital to become a milliner, an occupation requiring modest investment and little space to set up.

In a foretaste of her later work with serial repetition, Chanel used basic templates, such as the boater or wide brimmed straw hats which she dressed very simply. Her work struck a modern note and was popularised by actresses.

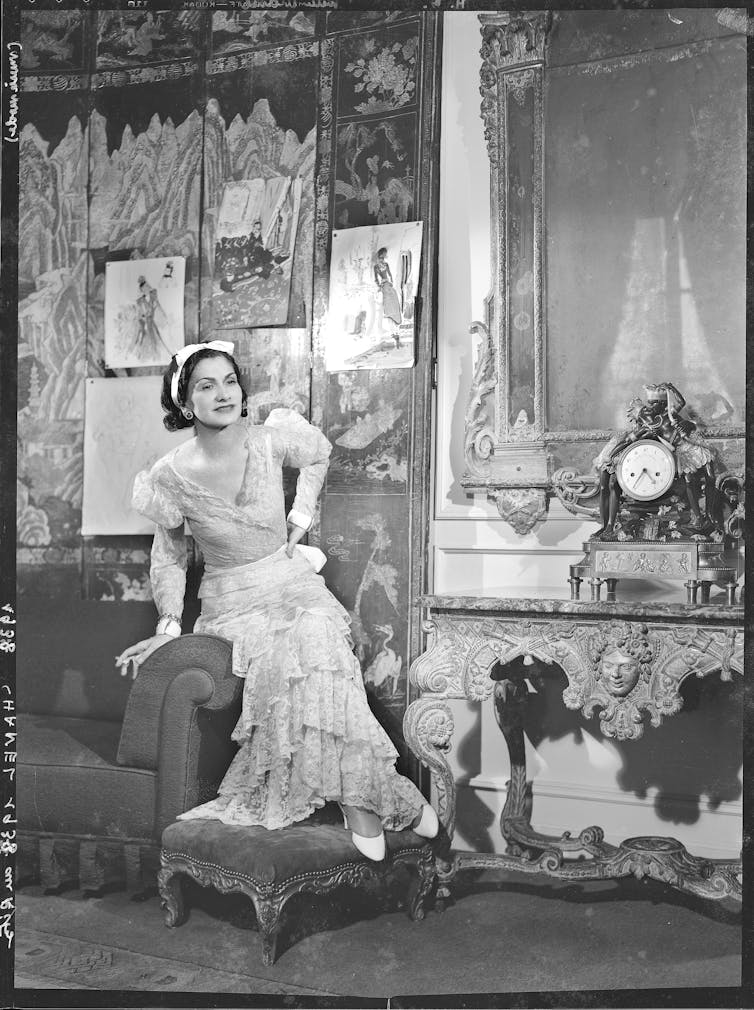

Courtesy of the National Gallery of Victoria

Making the modern woman

Chanel opened boutiques at Deauville and Biarritz, fashionable seaside resorts where she observed and wore beach garments made of the wool jersey that she later made her own signature. She took up with wealthy English men who introduced her to hunting dress and the Scottish tweeds that she also transformed into day wear for women.

We associate Chanel with the little black dress of the 1920s, which could be made of wool jersey for day or silk and tulle for evening. A short, tubular garment, it took the world by storm. Vogue called it the “Ford signed Chanel” in 1926, referring to the mass produced and affordable car that also came in only one colour.

The emphasis on the little black dress has distorted Chanel’s output, which always extended to vibrant but tonal colours, and other materials such as lace and satin for evening.

The little black dress also came from somewhere

The First World War brought with it the death of millions of young men, the disruption of succession in the great landed English estates, and the destruction of huge swathes of Europe. Cultural pessimism was common. Out went the lavish, historical styles associated with the robber barons and the Belle Époque.

France had the greatest casualties of WWI – nearly 2 million were dead. Chanel witnessed the collective mourning of thousands of French women dressed in black. She also saw the large numbers of women working in male occupations who suddenly wore uniforms with trousers, external pockets, overalls, and boiler suits.

The 1920s was a time of living for the moment and “experience culture”: sex, sport, travel, and fast-changing fashion. 1920s French women’s fashion was marked by a new engagement with the street and the notion of repetition. The Italian Futurists proposed cancelling fashion altogether. Chanel was ready for this change, even if her approach was more subtle.

In the 20th century the innovative silhouette and cut of clothes became the most important ambition for designers who wished to present new dress fashions. Cubist painters such as Picasso and Braque fractured the body. Their geometries were also adopted in clothing. Chanel both learned from and inspired the Paris modernist avant-gardes. The poet Colette remarked:

Chanel works with all ten fingers, with her nails, the side of her hand, her palm, pins and scissors, on the dress itself, a white mist with long pleats, spattered with flecks of crystal.

Chanel’s approach was modernist in that she was interested in the idea of a template for day-wear. In the late 1920s she made suits with unlined jackets revealing the selvedge (reinforced edge of the piece of fabric) and overstitching on the seaming.

Her monochrome palette which often used black, blue, red, beige and white was the opposite of the oriental sensuality of fashion design before the Great War. Her wide belts referred to both men’s wear and working wear, as did her famous striped matelots. From military dress she used the concept of the jacket’s lining extending to the revers, or lapel facings.

Installation view of Gabrielle Chanel. Fashion Manifesto from 4 December 2021 to 25 April 2022 at NGV International, Melbourne. Photo: Tom Ross

Chanel once noted: “One wears clothes with the shoulders. A dress should hang from the shoulders”. Like her older contemporary Madeleine Vionnet, she created dresses that seemed diaphanous and sculptural simultaneously. Her use of pin tucks created dresses that clung so closely to the body they appeared almost nude.

Her 1920s dresses appear deceptively simple but include skirts pieced together with up to 20 panels. Although she usually cut on the straight grain, Chanel made clever use of fabrics with tensile qualities, such as lace, tulle, jersey, chiffon, georgette, crepe de chine and loosely woven tweeds, blurring the distinction between the flou (dress-making) and the tailleur (tailoring) by applying techniques from each process to the other.

Chanel did not depart from the lines of the body. The focus on the Chanel suit has deflected attention from her evening wear of the 1930s, which is notable for its hyper-feminine effects using lace and sequins and suggestions of the bustle skirts of the 1870s.

Chanel was interested in a playful and conceptual design approach, in which real gems might be intermingled with fakes, and a practical pocket-book bag, first introduced in 1927, could hold everything a woman required for the day. There was no need to flaunt money in materials and craft, but luxury could be expressed in subtle ways that only other women might recognise.

Yet, this was no “democratic” move in any sense of the word. Chanel’s modern luxury was for those “in the know” and it continued to cost a great deal.

Read more:

Chanel’s new fragrance reminds us of the rebel entrepreneur who started it all

Chanel’s innovative luxury

Chanel was probably the person who contributed most to redefining luxury in the first half of the twentieth century.

We associate Chanel with the term chic, although this was not her invention. Théophile Gautier, the French journalist and literary critic, used the term in 1864, calling it “a dreadful and bizarre word of modern fabrication”.

With Chanel, chic came to mean an approach to style that was not simply dependent upon money, although money often helps. This explains her use of simple materials, muted colours, and rigid lines. She claimed that she was not interested in diamonds and pearls — many of hers were in fact fine fakes crafted by the jeweller Verdura.

Chanel’s concept of luxury had as its opposite, vulgarity. She was revolted by the approach to luxury connected with the vibrant Ballets Russes of the early 1910s and the associated fashions, perfumes, and household products retailed most notably by the fashion designer Paul Poiret:

The Ballets Russes were stage décor, not couture. I remember only too well saying to someone sitting beside me: “These colours are impossible. These women, I’m bloody well going to dress them in black”.

In the case of Chanel, clothes can been seen as dynamic forces that helped produce the “modern woman” – not the other way around, that is to say the women becoming modern and demanding fresh clothes.

Coco Chanel was among those at this time who argued that luxury was not necessarily physically embodied in artefacts: diamonds could therefore be replaced by imitation paste, silk or velvet by a wool jersey.

Chanel was partisan in a titanic struggle between the protectors of elite forms of luxury (today referred to as “metaluxury” or “über luxury”) and the growing middle class comforts and commodities of the time.

© Henry Clarke, Paris Musées / Palais Galliera / ADAGP. Copyright Agency, 2021

Chanel Number 5

Although known as a couturière, Chanel made her fortune from the sale of Chanel Number 5, a very expensive perfume made with the rarest luxury ingredients from the south of France but with the novelty of adding synthetic ingredients.

The base was an Imperial Russian scent whose heaviness was alleviated by the new aldehydes which gave a sharp floral and ylang ylang kick. It was first released in 1922 in its medicinal looking bottle, stripped of all historical association.

Sean Fennessy/ Gabrielle Chanel Fashion Manifesto

Chanel was not the sole author of these ideas regarding a luxurious simplicity. Clearly associated with wider aesthetic minimalism, they appear also in the popular writings of decorator Elsie de Wolfe, who wrote in 1913 that “the woman who wears paste jewels is not so conspicuously wrong as the woman who plasters herself with too many real jewels at the wrong time”.

Read more:

‘Smell like a woman, not a rose’: Chanel No. 5 100 years on, an iconic fragrance born from an orphanage

Luxury and the right wing

Chanel’s redefinition of luxury was part of a wider French debate about twentieth century taste and manufactures. One of her great loves was the French illustrator and entrepreneur Paul Iribe, who designed the famous art deco rose motif.

Iribe also ran a pro-nationalist magazine called The Witness (le Témoin) between 1933-35. Only red, white and blue ink, the colours of the French tri-couleur, was used in the printing. Iribe promoted the idea that France was the pre-eminent centre of luxury and criticised modern German and American design and also Jewish business. Iribe depicted Chanel as Marianne – saviour of the French, on one of the covers of The Witness.

Iribe was also behind an intriguing publication, the Defence of Luxury (1932), a printed manifesto that attacked aesthetic modernism, maintaining that France remained the centre of luxury despite the rise of other societies, particularly North America and Germany.

The Défense also had anti-Semitic and anti-cosmopolitan overtones, suggesting an international conspiracy was attempting to drive away the old value system that had created France as the pinnacle of luxury taste and style. Aristocracy and a “pure” French race were required, Iribe argued, in order for luxury manufacturing to continue.

Chanel’s designs, nonetheless, in their focus on craftsmanship, taste, and elite luxury (they were extremely expensive), were both a reaction to the state of affairs Iribe posited and also a confirmation Paris remained the centre of luxury.

Chanel’s own anti-Semitism, not uncommon for high-society elites of the time, came to stand as a shadow over the subtlety of her designs later in life, as did her relationship with high ranking Nazis, including her lover, during the Occupation of Paris.

Many claims, some disputed, have been made about Chanel’s level of collaboration with the Nazis, but she clearly benefited from her highly placed and opportunistic access to powerful people in France and England.

Chanel worked against the Wertheimer family who risked having their businesses Aryanised (sold to non-Jewish owners), partly because she resented the great profits they made from her house due to their earlier stock control. Following the war, enquiries were made into Chanel’s relationship with the Nazis and with the possible support of Winston Churchill (whose English aristocratic friend had been her lover) she retreated to Lausanne in Switzerland.

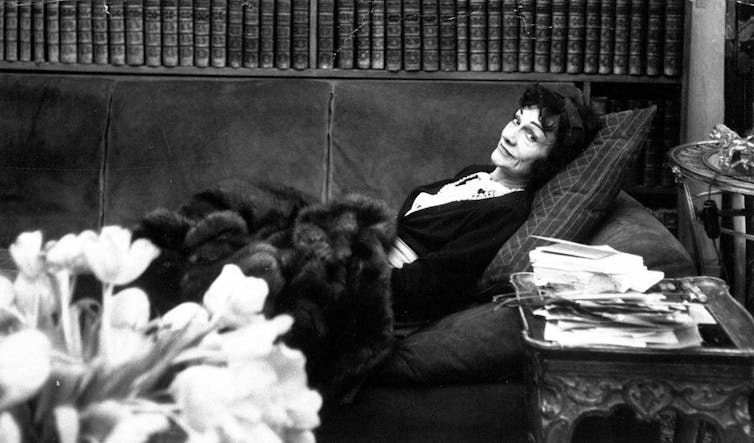

AP Photos

Chanel’s comeback

Returning to work in 1954, Chanel surprised everyone with the famous two piece Chanel suit, worn with a co-ordinating blouse. The irony of the template is that it could be modified with trims and details in order to maintain a sense of something fashionable and timeless (out of fashion) simultaneously. The cost of these simple looking clothes is indicated in a 1965 order for Marlene Dietrich: a white day suit cost US$6000, perhaps US$55,000 today.

DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University

The controlled and modernist Chanel chromatic was a striking foil to much 1960s fashion, particularly colourful and more revealing styles for women. Chanel herself once said that she would not be surprised if women might start showing their “ass” in the future; the sight of belly buttons and midriffs was enough to horrify her in the 1960s and 1970s.

Chanel would have been very puzzled by our contemporary bust ops and “facework”: she once said: “I can think of nothing more ageing than trying to make oneself look younger”.

Chanel died in 1971 aged 87. Let’s conclude by giving her the last word, in the grumpy attitude typical of many of her pronouncements of the 1960s:

I have dressed the whole world and, today, it goes about naked.